Portrait of a Lady

The Evolution of Female Portraits in Renaissance Italy

The Rise of Portraiture

Prior to the Renaissance, painted portraits were virtually unheard of. During the Gothic era, art was almost exclusively religious in nature, meaning no paintings of contemporary individuals were produced. So what changed?

In short, the rise of individualism and humanism. People were still deeply religious, but they began to place more importance on their humanity, and holy figures were no longer seen as untouchable icons. Art was no longer strictly religious, and artists began to paint personal paintings and scenes inspired by ancient mythology in addition to paintings for the church.

Portraiture began to naturally arise out of this philosophical shift. People suddenly became interested in recording their likenesses, or the face of someone they loved. However, Renaissance portraits were often full of symbolism, and strict cultural norms quickly arose around portraits, particularly female portraits.

This essay is going to look at a collection of female portraits throughout the High Renaissance to identify and analyze some of these trends.

Portrait of a Young Lady,

Sandro Botticelli (1485).

Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

Battista Sforza,

Piero della Francesca (1475).

Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Woman with a Man at a Casement,

Fra. Filippo Lippi (1440).

The Met, New York City, USA

Portrait of a Young Woman,

Sandro Botticelli (1480).

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Early Portraits and their Ancient Inspirations

What do all four of these women have in common? Most obvious is that they're all painted in profile. This isn't a coincidence, but a very intentional choice by the artists. This sharp profile pose was popular amongst men and women, and was meant to emulate ancient Roman coins. Throughout the Roman empire, the emperor and empress would put their face on coins, and would almost exclusively be shown in profile. For example, take a look at this Roman coin depicting the Empress Livia, wife of Augustus, the first emperor of Rome.

Portrait of a Young Lady takes the ancient inspiration a step further, and shows the subject wearing an ancient pendant, directly copied from a cameo in the Medici's personal collection.

The other notable element is the hairstyles featured in both of Botticelli's works and Francesca's Battista Sforza. The artists wanted to create idealized works with an element of fantasy to them, leading to incredibly detailed hair, clothes, and jewelry. Beauty was extremely important during this time as well, so the artists gave their subjects a highly idealized look and emphasized their pale skin and light colored hair.

Empress Livia on a Coin, (22-23 AD).The British Museum, London, England

Lady with an Ermine,

Leonardo da Vinci (1491)

Czartoryski Museum, Kraków, Poland

Young Woman with a Unicorn,

Raphael (1506)

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

La Belle Ferronnière,

Leonardo da Vinci (1496)

The Louvre, Paris, France

Maddalena Doni,

Raphael (1506)

Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

The Three-Quarters Pose & Animal Companions

Eventually, the three quarters pose became popular, and portraits became less fantastical and more lifelike. Expensive jewelry and clothing also remained popular, as those with enough money to commission portraits wanted to display their wealth.

In female portraiture, there was also an emphasis on communicating the virtue of the sitter. External beauty was often linked to virtue, so artists continued to idealize their subjects. They also often painted women in interior settings, and the women often wore simple, restrictive hairstyles that were meant to 'contain' them. Finally, the women avoid eye contact with the viewer, looking off to the side instead of directly out. This also would have been understood as a sign of their purity.

Animals in portraits were also related to a woman's virtue. The two most famous examples, Lady with an Ermine and Young Woman with a Unicorn, show us women holding two rather unusual animals. A unicorn is perhaps a more obvious symbol of purity, as medieval legend stated that only a virgin could touch a unicorn. The ermine seems like an unusual choice, but sends a similar message. Ermines have a reputation for keeping their pure white fur clean, so the inclusion of an ermine alludes to the woman's virginity. However, ermines are also aggressive animals, so the creature could also be protecting his mistress from potential suitors.

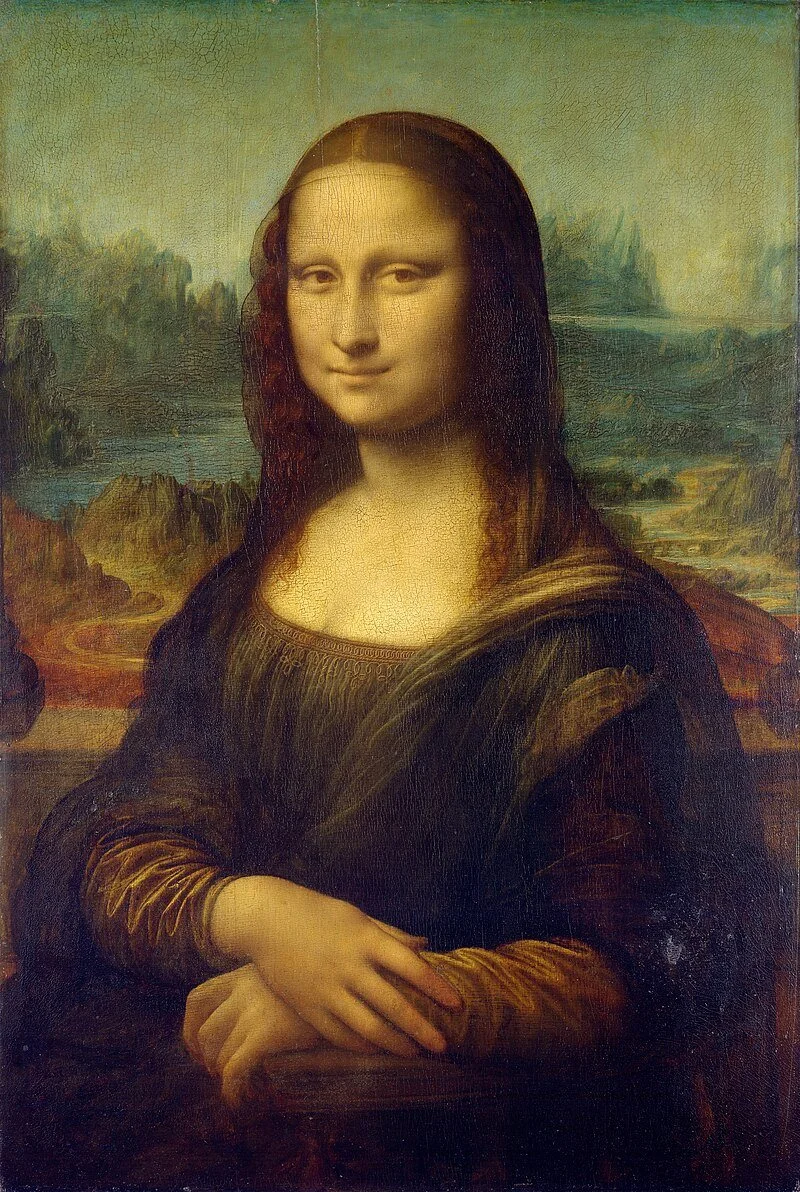

Mona Lisa: A Revolutionary Portrait

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is quite possibly the most famous painting in history. Part of the reason it is so famous is that, when it was first painted, Mona Lisa was considered a revolutionary portrait.

First, the landscape behind her was different from anything seen before. This isn't the first female portrait set outside, but the landscape is much more complex than any other portraits.

Second, she is looking directly out of her portrait. Her eyes have even been described to follow the viewer. This was 'acceptable' because Mona Lisa was commissioned by the subject's husband, and wasn't meant for public viewing, so it wasn't considered scandalous for her to look directly out of her portrait. Additionally, the positioning of her hands marks her as a faithful wife, even though she does not wear a wedding ring.

Mona Lisa looks less lifelike now than it did when it was originally painted. The aging varnish over the paint gives the whole work a dark green cast, and cannot be cleaned due to the delicacy of the painting. However, when Georgio Vasari saw Mona Lisa, he praised the work for its extreme realism. He even describes the famous smile, writing “And in this work of Leonardo there was a smile so pleasing, that it was a thing more divine than human to behold, and it was held to be something marvelous, in that it was not other than alive.”

Mona Lisa inspired many portraits, including Raphael's Young Woman with a Unicorn, and Leonardo's workshop also produced several copies.

Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci (1508)

The Louvre, Paris, France